-

Day 13. Portland to Middlebury

In which we travel the back roads of the Granite State, visit a historical hotel, sip syrup and try beer soup

As I mentioned in yesterday’s blog, driving on freeways and interstate highways is kind of boring. If you are in a rush, sure, it’s the fastest way to get there, it’s smooth and low-stress. But all you get to see is the cutting the highway is going through, or the trees planted on the side of the road, or the next in the seemingly endless – and endlessly repetitive – series of petrol station and fast-food outlet rest stops. It’s dull. If you really want to see the country, the interstate will not show it to you.

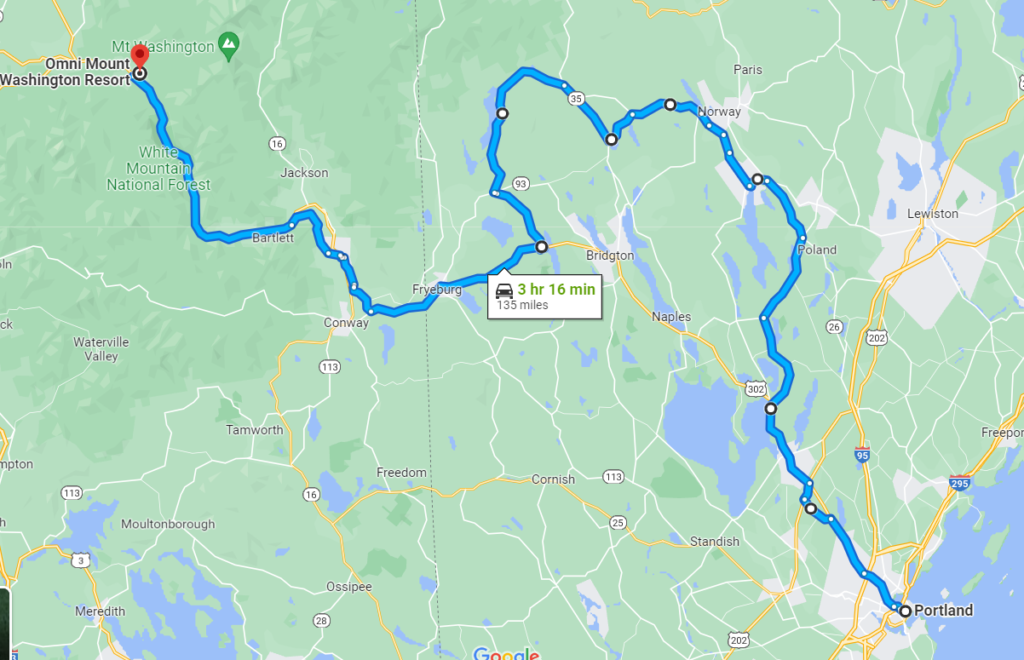

And, as it happened, there is no interstate heading west/north-west from Portland to where we wanted to go. So we started off on Route 302 and kind of wandered our way through the lakes and hills of western Maine.

The map above is just an approximation, we left the state routes and wandered along country roads as the mood took us. We kept heading generally west, with an eye on the time so we could be at Mount Washington for lunchtime.

And we stopped as the mood took us, also. Such as by a river …

… or by a different river, seen through some trees …

… or another river, seen through the railings on a bridge. Yes, they have a lot of rivers! And don’t worry, it was a very quiet road and there were no cars around except ours, we were being very safe. And see that tiny little flash of bright red there! We were sadly a couple of weeks too early for the real New England fall foliage display, but there was a hint here and there of what it might look like.

For a change, we stopped by one of the approximately 6,000 lakes of Maine. And no, we don’t know this one’s name.

Maybe I need a better camera. I swear the view of clouds pooling over the top of the range of hills was a lot more majestic than it looks here.

Mr Cow on a hillside in Maine, looking toward far horizons. He really does have the brooding presence of a young Brando, doesn’t he?

And we stopped to get petrol, of course, and we looked on the shelves of the gas station to see what we could see.

To our Australian readers, Alpo – to the left of the photo – is an American brand of dog food. Chef Boyardee – to the right – is a brand of human food. But it is remarkable, when you see them together, just how similar the packaging is, and how close they are on the shelf.

I see no possible way that could cause a problem.

And eventually we arrived at the Mount Washington resort, also known as the Bretton Woods hotel.

It’s a big, beautiful building in that very classic resort hotel style. It was built in 1900-1902 and has 269 guest rooms. In summer you can bike, hike, golf and fish, and in winter you can ski, snowboard, skate and apparently even go dog-sledding. We had lunch at Stickney’s, the pub/steakhouse in the hotel, and there’s a formal restaurant and several bars. If you’re not staying at the hotel it’s wise to book as, quite sensibly, hotel guests get first priority for tables.

The foyer is vast, and elegant in a simple and tasteful way. The Breakers it ain’t!

The hotel is big enough to have its own Post Office branch. Or maybe it’s just that the guests were influential enough.

But aside from looking kind of like the inspiration for the hotel in The Shining (it wasn’t, although there is a passing similarity), Mt Washington Resort is most famous for the Bretton Woods conference that took place here in 1944.

The conference brought together senior finance ministers and officials from the members of the nascent United Nations, to design a post-war international financial structure. This would, hopefully, avoid the scourges of hyperinflation, trade wars and financial depression that had plagued the interwar years. The result was the establishment of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and a system of free currency interchangeability and pegged but adjustable exchange rates. This provided international economic stability, more or less, for nearly thirty years until the oil crisis of the mid-1970s, when it fell apart in a series of, well, inflation, trade wars, and finally stagflation which was only broken by a series of forced recessions. So let’s call that a qualified success.

The conference itself was another of those epic stories of financial and political shenanigans of the highest order. On the British delegation was John Maynard Keynes, the brilliant upper-class academic with a view of a radically egalitarian post-War financial order which would, coincidentally, keep Britain in its place as a pre-eminent financial power. On the American side was Harry Dexter White, a working class child of poor immigrants who didn’t complete college until his thirties, clever and methodical, a secret Communist sympathiser* who nevertheless set out to cement the US in the top spot, which involved removing Britain to a lower place.

The conference itself was a festival of bureaucratic dirty tricks including last minute agenda changes, reallocating policies between sub-committees until no-one knew who was approving what, and ultimately delivering the final treaty the night before signing with a few key alterations, leaving inadequate time for review**. We may think modern politics is dirty, but these old-timers were as sneaky as they come.

Spoiler : the Americans won. Making the US dollar the defacto currency of international trade put America at the top of the international financial heap for half a century and more, and they are in many respects still there.

And the conference room where the final signing took place has been preserved so that economics tragics like myself can visit and be dazzled by the lingering aura of history being made.

* White, among other things, provided details of American economic statistics and financial policy plans to the Soviet embassy in Washington DC. In return, crates of Russian vodka and Crimean champagne were left on his doorstep in the middle of the night. It was a simpler time.

** For a detailed history of the events, I can recommend The Battle Of Bretton Woods by Ben Steil.

This is my dazzled face Outside the Gold Room where the signing took place.

A list of all the senior delegates. I’m not quite sure why Canada had a senior rep there but Australia didn’t.

A display case with the flags of the attendees. I’m not sure if these are original or came later.

Mr Cow, basking in the auras.

The view from the front porch of the hotel is spectacular.

The hotel has its own golf course, of course, and you can see the ski runs on the hills across the road. And some red leaves! These are probably the reddest we saw on our trip, but let’s keep our eyes peeled as we go.

As we left we stopped for a last look at the hotel.

Our next leg of the day was to scoot through some more hills and mountains to get to Bragg Farm Sugar House, which is an old fashioned maple syrup farm. As I always say, when in Vermont, take some time to stop and taste the syrup.

Hills and mountains and country roads. The Mighty Sentra was not a great driving car by any shake of the stick, but this was a fun drive. Windy enough to be engaging (but not enough to be scary), and picturesque views around every bend.

Doreen : It was now getting towards late afternoon and while the scenery was lovely, I was a bit concerned we might arrive too late for my Vermont bucket list stop – Maple syrup sampling.

At Bragg Farm the Maple Sugaring or “sugaring” process of collecting the sap from maple trees and concentrating it into syrup is still done in the traditional way, tapping the trees by hand and collecting the sap in buckets. The season is from February to April and is weather dependent, requiring freezing night temperatures and a daytime thaw of about 5 degree Celsius for the sap to flow. It takes forty years before a tree can be tapped, and after that it can be done every year (in a different place on the tree) for as long as the tree is healthy which can be around 400 years.

The evaporator boils the sap containing 1-5% sugar concentration into syrup of around 66%. It takes many hours (1 hour per gallon) to condense the sap and from 44 gallons you get just one gallon (3.78 litres*) of syrup. On average a tree will produce between 10 – 20 gallons a season. If you want to see more of Bragg Farm visit youtube or see the current manufacturing process done by the Maple Guild.

* Yes, I know a gallon is 4.55 litres. American gallons are smaller because their pints are smaller, 16 fluid ounces instead of 20. So, if you are from the Commonwealth, just multiply the American gallon amount by 0.8308. Simple!

We bought a Maple Grading Sampler as a gift and a bottle of Very Dark Grade A. The syrup colour depends on on when it is collected, the later the season the darker the hue. It has been sitting in our cupboard for 3 years awaiting the right occasion or recipe to entice us, as once opened it needs to be refrigerated. However I have just read it can be kept indefinitely, frozen. Hmm so maybe pancakes are on the horizon soon . .

Back to David : It was a busy day with lots of driving. Too long, really, six hours is absolutely the most you should drive if you want to see anything along the way. And ideally four or so. By the time we got to Middlbury it was sunset* so we didn’t have time for a look around.

We had booked in to the Middlebury Inn, a lovely old-fashioned venue nearly two hundred years old. We dropped our bags, freshened up and went in search of dinner.

* The photo above is from the next morning.

We ended up at the Two Brothers Tavern, a handy 10 minute or so walk from the inn. There was a bustling bar but we felt like a bit of quiet after a long day, and retreated to the less populous and rather more peaceful dining room for our dinner.

America has benefited from a brewing boom in the last few decades. Jokes about their beer being like making love in a canoe are well past their use-by date. Lawson’s Scrag Mountain Pils is a Pilsener-style beer, crisp and fresh with mild floral hops. It was delightful at the end of a long day’s drive.

And New England has been known for cider for as long as anyone can recall. Woodchuck Granny Smith Hard Cider is dry, light-bodied and tangy, and goes down a treat.

And Vermont is also known for its cheese. Put artisinal cheese and a strong brewing tradition together and you get beer and cheese soup (at the top of the photo), made from Cabot cheddar and Switchback ale. It was full-bodied but not heavy, and Doreen has asked me to make it a few times since we came back.

And at the bottom of the shot is a Plaid Salad, with red and golden beets, candied walnuts and crumbled sharp cheddar, Granny Smith apples and scads of healthy kale. Tourist tip – burgers and fries are yummy, but look after your body and have some greens now and then.

So that’s it for another day. Tomorrow we have a walk around Middlebury, visit a fortress that never was, and may or may not see a giant lake snake!